Summer of Soul: A review

March 9, 2022

It’s the summer of 1969. Music is booming, fashion is changing, and the world seems to be turning upside down. Most people think of Woodstock as the major event of that year. But what if I told you there was another festival that same year, a festival including such icons as Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, and B.B. King, a celebration of Black culture, music, and beauty?

That is exactly what occurred from June 29th to August 24th. The Harlem Cultural Festival took place in Mount Morris Park, right in the middle of New York City. The event brought in over 300,000 people to see some of the greatest artists of the time. Thanks to the event’s coordinator and curator, Tony Lawrence, the festival was free to all and was an incredible success. The entire festival was filmed, so why has no one heard of it before?

Filmmakers attempted to sell and distribute the footage after the fact, but no one bought it. Not a single company thought it was worth producing. In many ways Woodstock overshadowed the Harlem Cultural Festival, and so the event was essentially forgotten, left in the 60s. 50 years later, the footage was found sitting in a basement, and The Roots’ lead band-member Questlove decided to do something about it.

And so the film Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) was born in 2021. Directed and produced by Questlove, the film resurfaces the footage of the Harlem Cultural Festival along with testimonies from those who attended, and even those who performed.

Color jumps out of the screen in a symphony of light and the music hits you with a stunning power. Standout artists include Stevie Wonder, who plays the drums in a whirlwind of rhythm and sings with that iconic twang. The 5th Dimensions discuss how they walked the line between white and Black popular culture, and how they unapologetically created. B.B. King’s blues emanates emotion, and the final performance of Nina Simone’s Backlash Blues hits the soul perfectly. And that is just the half of it. The film beautifully puts the festival into context of the 1960s, highlighting what this time in history meant for Black people across America.

The year of 1969 was a year of revolution for the Black community. The Black Panthers were at their peak, fighting for the rights and the protection of their people. They policied the festival itself, as the NYPD decided it was not worthy of protection. The death of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X had a profound impact that led to strife and pain within the Civil Rights Movement. Black Americans were fed up, and music became the driving force of revolution, healing, and unification.

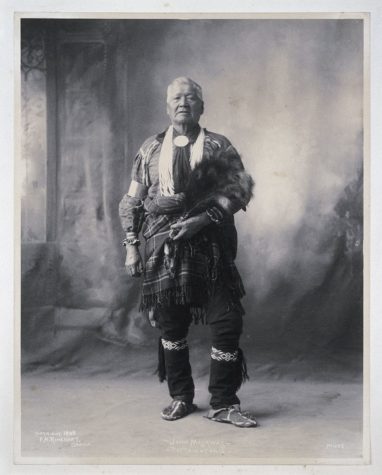

The 60s were a time of empowerment and reinvention for the Black community. For the first time the term “Black” was being used. To be Black was synonymous with being powerful, and to be Black meant reclaiming your roots. Afros were in style, and African garments were worn in reverence of shared history. Music became a space for reclaiming culture, as African influence boomed and music was a vehicle in which Black power and protest was spread.

The festival was a time of triumph, a celebration of the beauty of Black culture. As a festival attendee states, “It was like seeing royalty”. The sea of Black New Yorkers coming together was a symbol of hope, a moment of love and joy. For so many years the Black community in Harlem has been overlooked, but this festival reminded Harlem of what makes it special: the people.

And that meant all of Harlem. The documentary highlights how the Black revolution and the Latine revolution went hand in hand. New Yorican (Puerto Rican New Yorkers) artists such as Ray Barretto are featured at the festival, and the film makes sure to acknowledge how the communities worked together to create change. This is something rarely portrayed, as many times minority groups are pitted against each other. Yet in this moment, the festival celebrated that union, and made all feel accepted.

To see some of the greatest Black artists of all time in such clear audio and visuals has an impact that can not be understated. For many the film is affirming by showing Black excellence on the big screen. Jamal English, LFA English teacher, poet, and musician says it best, “When I look at that documentary, it reminds me of the deep, still, watery source, from which I draw the resilience”. English views music as the “homeopathic medicine” for the Black community, essentially a therapy that cures within a society designed to destroy his culture.

This outlook is in tandem with religion, as gospel is a kind of therapy. Gospel was one of the only ways in which slaves and freedmen could express themselves, and continues to be a way in which the Black community connects. Spirit possession, during which a person connects to the music and spirits, is a kind of medicine, a connection to freedom and oneself. In the film Mahalia Jackson, one of the greatest gospel singers of all time, screams the word of God in a song of freedom and faith. The honoring of Martin Luther King Jr. with his favorite gospel Precious Lord brings tears to one’s eyes, and shows just how connected religion and revolution are.

Summer of Soul will have a lasting impact, and rightfully so. The documentary lets the raw footage shine. It is a celebration of Black joy. But most importantly, it brings representation and Black stories to the forefront. As English states, “When I saw it, I saw me.”