The Great Resignation: America’s dwindling workforce

February 3, 2022

Breaking news—the pandemic has claimed another victim. This time, it’s the American workforce.

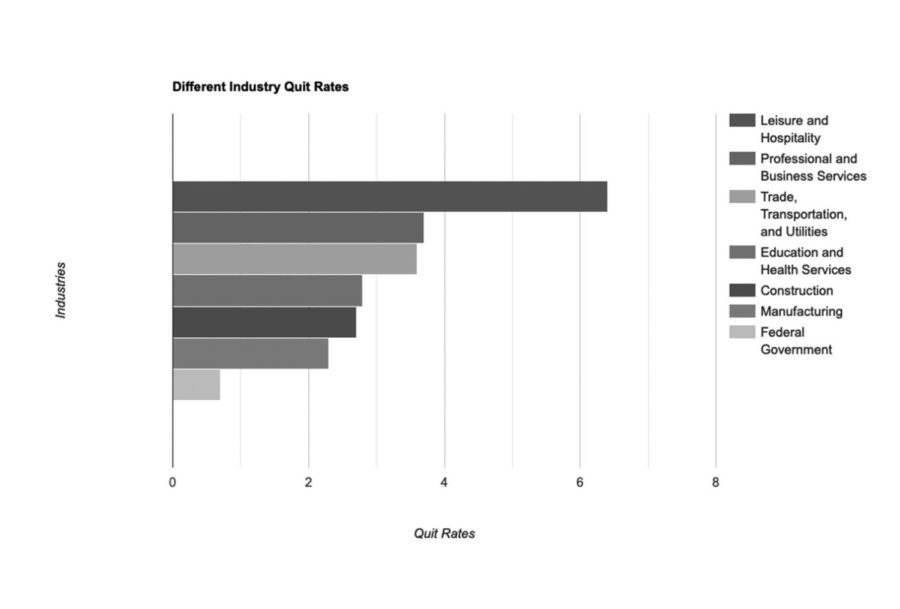

They call it “The Great Resignation”—millions of Americans are quitting their jobs, and many have no intention of seeking future employment.

Working conditions in the United States have continued to worsen throughout the pandemic, prompting many Americans to simply call it quits. They express that they feel unsafe, unmotivated, and unsupported. The movement has been detrimental to both America’s working culture and economy.

At a first glance, the statistics could fool any untrained eye. According to the U.S. Department of Labour, the nationwide unemployment rate sits at a staggeringly low 3.9% as of December 2021. However, this number is far from accurate.

In defining the term “unemployment rate,” Lake Forest Academy’s economics teacher, Matt Vaughn, said, “The only ones who are counted are the ones who are looking for jobs.” This fact is crucial to consider when citing the statistic.

Instead, Vaughn urges students to consider another, more representative statistic—the labour force participation rate. This tracks the number of people who are either employed or looking for employment within a population.

The U.S. Department of Labour has stated that the labour force participation rate in America is 61.9% as of December 2021. Pre-pandemic (as of 2019), the rate was 63.6%. This statistic highlights a slight—but not insignificant—decline in labour force participation across the country.

The numbers—though noteworthy—do not express the true extent to which this situation has impacted the country.

Wages have increased—many of those who are seeking employment standby for offers of higher pay. As Vaughn describes it, “[people] keep thinking that they can get higher and higher wages at lower skilled jobs.” Yet, this puts businesses in a difficult position, as they need employees, but cannot afford to pay the rates that are necessary to keep them. Vaughn’s advice for those awaiting such wages is to “Take that 17, 22 dollars, 28 dollars an hour and run.”

Another issue lies in the concept of structural unemployment—a result of the present disconnect between the structure and the economy in the United States. As the demand for labour in America shifts, so do the jobs. Many people who are entering the workforce are not prepared for the occupations that the economy has begun to value. Some might be overqualified, and others underqualified. To know what jobs are actually needed in the economy right now, the dust needs to settle.

Vaughn paints a picture of what this looks like on a micro level—“Some people are saying ‘you know what, I have a college education. I’m not going to go work as a dishwasher and make $22 an hour.’”

Beyond the detriment to the economy lies the radical change in America’s working culture.

The significant increase in early retirement has prematurely accelerated many career paths, and sacrificed mentorship from those in senior positions. In the past, these people would’ve slowly transitioned out of work, putting in fewer hours in exchange for a little time on the golf course. Now, many are taking a more abrupt route of resignation. As a result, the remainder of the workforce lacks a critical aspect to their careers—experience.

American working culture has also faced a detrimental blow to the definition of a valid occupation on a fundamental level. As the country’s workforce begins to take on new blood, companies and individuals alike are forced to face the consequences that have come with online schooling. These issues are only expected to become more prevalent as youth in the United States continue to transition to adulthood, and the gaps in their education prove to have robbed them of crucial foundational knowledge.

Today, this lack of proper education in American youth is evident across the country, and the situation does not bode well for the future of the workforce, the economy, and the potential for upward mobility.

So, what exactly does the future look like? Our world, as it currently exists, is anything but predictable. Right now, anyone who wants a job can get a job, and therein lies the irony. The idea of what qualifies as a valid job has completely deteriorated. Working culture in the United States has faced a complete upheaval. As Vaughn says, “It’s not just a black and white issue.”